Motivation is the internal and external forces that stimulate people to take actions towards a goal. A motivated workforce is more productive, delivers better quality and is less likely to leave the organisation.

Why motivation matters

Motivated employees are willing to work hard and use their initiative. They have higher morale, produce better quality work, are more loyal and less likely to be absent. High motivation can reduce recruitment costs and enhance a firm’s reputation as a good employer.

Motivation theories

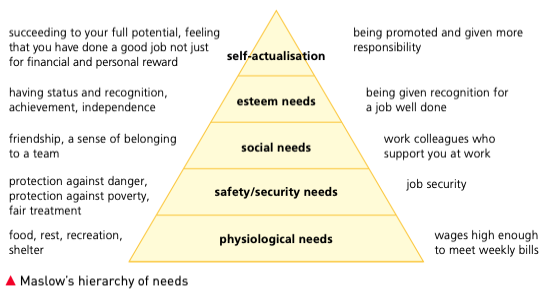

- Mazlow’s hierarchy of needs – People are motivated by a hierarchy: physiological needs (food and shelter), safety needs (job security), social needs (sense of belonging), esteem needs (recognition) and self‑actualisation (achieving one’s potential). Employers should aim to satisfy needs at each level.

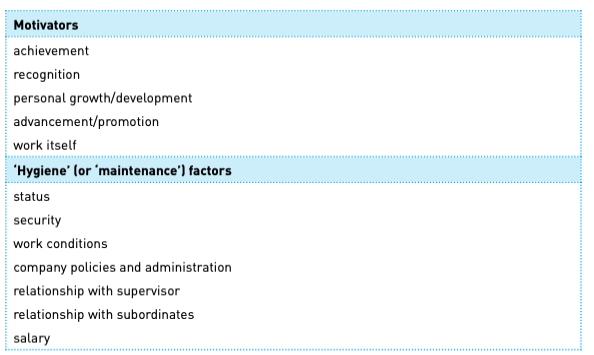

- Herzberg’s two‑factor theory – Distinguishes hygiene factors (pay, working conditions) that prevent dissatisfaction and motivators (achievement, responsibility) that actively create satisfaction. Improving hygiene factors alone will not motivate employees; providing meaningful work is also necessary.

- Taylor’s scientific management – Believes workers are mainly motivated by money. It advocates setting output targets and paying piece rates to encourage higher productivity.

| Theory | Key idea | Implications for managers | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maslow’s hierarchy of needs | Individuals have a hierarchy of needs; lower‑level needs must be satisfied before higher‑level needs motivate. | Pay fair wages (physiological/safety); create a supportive team culture (social); recognise achievements (esteem); provide opportunities for personal growth (self‑actualisation). | Not all employees value needs in the same order; cultural differences may affect applicability. |

| Herzberg’s two‑factor theory | Differentiates hygiene factors (prevent dissatisfaction) from motivators (drive satisfaction). | Ensure good working conditions and fair pay to remove dissatisfaction; design jobs with challenge, responsibility and recognition to motivate. | Some factors may act as both hygiene and motivator; research was limited to specific professions. |

| Taylor’s scientific management | Money is the primary motivator; productivity increases when workers are paid piece rates. | Set clear output targets and reward achievement financially; break tasks into simple, repetitive elements. | Overlooks social and psychological needs; may reduce work quality and creativity. |

Financial methods of motivation

Financial rewards can encourage employees to work harder. Options include:

- Time‑based pay – wages (hourly) and salaries (annual). Overtime pay compensates extra hours.

- Piece‑rate pay – payment per unit produced, encouraging speed but possibly reducing quality.

- Commission – payment based on a percentage of sales made; common in sales roles.

- Bonus schemes – one‑off payments for meeting targets.

- Profit sharing – distributing a share of company profits among employees.

- Share ownership – giving employees shares or options to align their interests with shareholders.

- Performance‑related pay – linking pay rises to an individual’s performance appraisal.

Non‑financial methods of motivation

Many people value factors other than money. Employers can motivate staff by:

- Job rotation – moving employees between tasks to reduce boredom and widen skills.

- Job enlargement – increasing the range of duties at a similar level of responsibility.

- Job enrichment – adding more challenging tasks and giving employees more control over how they work.

- Empowerment – delegating authority and allowing staff to make decisions.

- Teamworking – encouraging employees to work in groups to achieve common goals.

- Training and development – improving skills makes jobs more interesting and helps career progression.

- Praise and recognition – positive feedback, employee of the month schemes and awards.

| Method | Type | Main benefits | Possible drawbacks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Piece‑rate pay | Financial | Encourages high output; links pay to effort. | May reduce quality; could demotivate if rate is low. |

| Bonus/commission | Financial | Rewards good performance; incentivises sales. | Unpredictable income; may encourage aggressive selling. |

| Profit sharing/share ownership | Financial | Aligns employee and company goals; fosters loyalty. | Dependent on overall company performance. |

| Job rotation | Non‑financial | Reduces boredom; broadens skills. | Initial fall in productivity as staff learn new tasks. |

| Job enrichment/empowerment | Non‑financial | Increases responsibility and autonomy; develops skills. | Requires training; may not suit all employees. |

| Teamworking | Non‑financial | Encourages collaboration and social needs. | Group conflict may arise; free‑rider problem. |

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs

The graph below illustrates Maslow’s theory, showing how needs build upon each other. Employers should try to satisfy lower‑level needs before higher‑level motivators become effective.

Herzberg’s two‑factor theory diagram

The two‑factor theory distinguishes between motivators and hygiene factors. Motivators such as achievement, recognition and personal growth create job satisfaction, while hygiene factors like working conditions and salary prevent dissatisfaction. The diagram below summarises this approach.

Examples and applications

Many organisations combine financial and non‑financial incentives to motivate staff. For example, a call centre might offer monthly bonuses to employees who handle the most customer enquiries, while also providing regular praise and opportunities for promotion. A technology company such as Google provides free meals, creative workspaces, flexible hours and autonomy to encourage innovation and job satisfaction. Meanwhile, a small manufacturing firm might introduce job rotation and teamworking to make routine tasks more interesting. These examples show that one size does not fit all: managers must choose motivation methods suited to the nature of the work and the needs of their employees.