Definitions and measurement

Inflation is a sustained increase in the general price level of an economy. Deflation is a sustained decrease in the general price level. Disinflation occurs when the rate of inflation slows but prices are still rising. The inflation rate is typically measured using a consumer price index (CPI), which tracks the prices of a basket of goods and services.

The inflation rate can be calculated as:

Inflation rate (%) = ((CPIt − CPIt−1) / CPIt−1) × 100

Causes of inflation and deflation

- Demand‑pull inflation – occurs when aggregate demand grows faster than aggregate supply, bidding up prices.

- Cost‑push inflation – caused by rising costs of production (e.g. wages, raw materials), which firms pass on to consumers.

- Built‑in inflation – when workers demand higher wages to keep up with inflation, creating a wage–price spiral.

- Deflation can result from weak demand, technological progress leading to lower costs, or tight monetary policy. Persistent deflation can discourage spending because consumers expect prices to fall further.

Consequences

| Inflation | Deflation | |

|---|---|---|

| Purchasing power | Reduces real value of money and savings | Increases real value of money; may increase debt burden |

| Uncertainty | High and unpredictable inflation discourages investment | Deflation can lead to delayed consumption and investment |

| Distributional effects | Hurts people on fixed incomes; benefits borrowers | Benefits savers; hurts debtors and firms with fixed nominal prices |

| Exports and imports | High inflation makes exports less competitive; imports become relatively cheaper | Deflation may improve competitiveness if domestic prices fall relative to foreign prices |

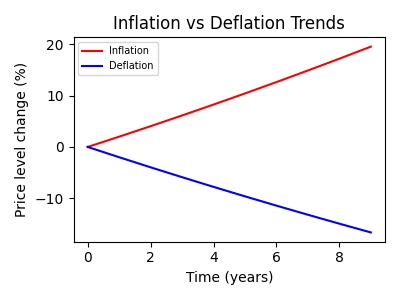

Illustrating inflation and deflation

The chart below shows stylised inflationary and deflationary trends over time.

Controlling inflation and deflation

Governments and central banks use monetary, fiscal and supply‑side policies to control inflation and prevent deflation:

- Monetary policy – raising interest rates and restricting the money supply to reduce inflation; lowering rates to combat deflation.

- Fiscal policy – reducing government spending or raising taxes to cool an overheating economy; increasing spending to boost demand during deflation.

- Supply‑side measures – improving productivity and competition to lower production costs and prices.

Examples and applications

Hyperinflation provides a vivid example of the costs of uncontrolled price rises. In Zimbabwe in the late 2000s, inflation spiralled into billions of percent per year as the government printed money to finance spending. Prices rose daily, savings became worthless and the economy collapsed until a new currency was adopted.

On the other hand, deflation has been a persistent problem in Japan since the 1990s. Consumers delayed purchases expecting prices to fall, slowing economic growth. The government and central bank have struggled to raise inflation to their 2% target despite low interest rates and fiscal stimulus.

Moderate inflation can benefit debtors because it reduces the real value of outstanding loans, while high inflation hurts people on fixed incomes. Conversely, deflation increases the real burden of debt, which can discourage borrowing and investment.

Calculation example

Assume the consumer price index (CPI) rises from 150 in year 1 to 159 in year 2. The percentage change in prices is:

Inflation rate (%) = ((159 − 150) / 150) × 100 = 6%

A 6% inflation rate means that, on average, prices have increased by 6% over the year. If the CPI falls from 150 to 147, the calculation ((147 − 150) / 150) × 100 gives −2%, indicating a deflation rate of 2%.